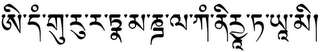

The mantra reads:

idaṃ guru-ratna-maṇḍalakaṃ niryātayāmi

इदं गुरुरत्नमण्डलकं निर्यातयामि

(above in dbu-can)

इदं गुरुरत्नमण्डलकं निर्यातयामि

(above in dbu-can)

If we take this to be a Sanskrit sentence then the words guru and ratna are undeclined suggesting that they are part of a compound: gururatnamaṇḍalakaṃ. So how should be parse this compound? Firstly the individual words: guru = teacher; ratna = jewel; maṇḍalaka is a variant of maṇḍala. The -ṃ ending would appear to match the idaṃ and be an accusative making idaṃ gururatnamaṇḍalakaṃ the object of the verb. I suggest that we take ratnamaṇḍalaka to be a tatpuruṣa - maṇḍala of jewels. Then it would make some sense for this to make a tatpuruṣa with 'guru', but perhaps of the dative kind, 'to or for the guru' rather than the standard genitive 'of the guru'. Looking at the context I think this fits what is being done in practice.

The verb comes from the root √yat 'to stretch'. What we have here is a causative form: yātayati which can mean 'to suffer', or in this case 'to yield up' or 'surrender'. The first person singular is yātayāmi 'I surrender'. The addition of the prefix nir- here indicates that one is giving up to others. Of Monier-Williams' suggestions 'to give back, to restore' seem to fit the context, he notes the sense of 'to give as a present' in the Lalitavistara Sūtra.

So we could render the phrase

idaṃ guru-ratna-maṇḍalakaṃ niryātayāmi

I offer up this jewel-maṇḍala to the guru

I offer up this jewel-maṇḍala to the guru

I find it disheartening that we don't even know what many of these phrases mean that actually have translatable meanings (as opposed to the other sort).

ReplyDeleteIt also causes me to wonder: Why use a mantra that has no known meaning?

Hi Al,

ReplyDeleteYes. We accept the blanket statement that mantras cannot be translated, but often they can to some extent.

I suppose mantras always had some 'meaning' when they were first used, but that this was lost sight of over time. I suspect, though, that purpose was more important than meaning - echoing the big debate of 20th century linguistics between the semanticists and the pragmatists. The siddhas were interested in what the mantra did, and not concerned to make sense of the words if they did the magic.

Recalling that Buddhists rejected the 'vibrations' and 'divine words' theories of the Brahmins we have some catching up to do in explaining what we think we are doing with mantras.

A lot of it boils down to considering the deity mantra to be a form of the name of the deity and chanting the mantra an expression of devotion and śraddha - which according to early Mahāyāna sutras has a salvific value.

Mantras such as this one are like stage directions for tantric rituals - which is why they are more or less just phrases in Sanskrit.

I hope to have more to say on this as time goes on - there is some pressure building!

Regards

Jayarava

Thank you for the mantra !

ReplyDelete